Souls of SOLS, April 2025: Highlighting Graduate Student Stories

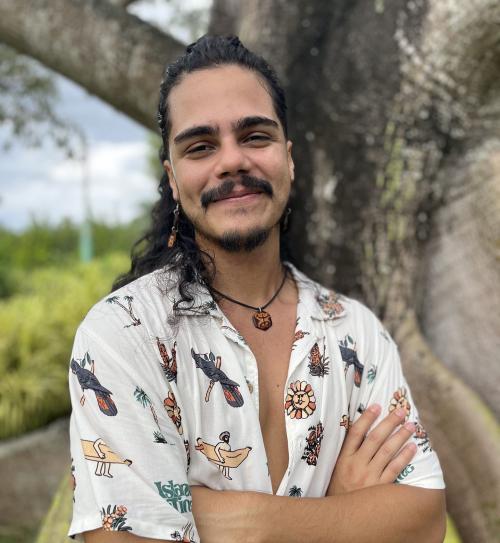

Marc Fóntanez Ortiz, left, is a PhD student in the Environmental Life Sciences program. Victoria Carvajal, right, is a master's student in the Biology and Society program.

Note: This story is part of an ongoing series profiling graduate students in the School of Life Sciences. See January's featured students here.

Marc Fontánez Ortiz – Environmental Life Sciences PhD

Marc Fontánez Ortiz, a PhD student in the Environmental Life Science program, never could have pictured what his career would look like.

“Even though I was raised on an island and had a strong connection to the ocean, I never saw myself as a scientist,” Fontánez shares.

But when he started his undergraduate degree at the University of Puerto Rico, he couldn’t help but be drawn to the field.

“I decided, “You know what? I think I like this thing called Science.” I like to be outside. I like to get dirty, to be in nature. That’s my thing.”

Microbiology in particular was fascinating to Fontánez. At the end of his bachelor’s degree, he was accepted into the Woods Hole Partnership Education Program, a fellowship through which he got to study marine subsurface microbiology in Massachusetts.

“That was an amazing opportunity,” Fontánez shares, “I got so overwhelmed with different topics I’d never heard of, like the deep sea [ecosystem] –– it was so obscure to me, and very exciting. That motivated me to continue into an ocean science career.”

Fontánez applied to multiple graduate degree programs afterwards, but wasn’t accepted into any. Not giving up, he moved in with a friend, Mahmoud Matar Abed, in Arizona, started working as a waiter, and spent his free time knocking on the doors of all the ASU scientists who did research he found exciting. Eventually, he knocked on microbial ecologist Hinsby Cadillo Quiroz and oceanographer Susanne Neuer’s doors, who gave Fontánez a chance. As part of a shared project, Fontánez studied the microbiology of marine particles. That opened the door for him to pursue a master’s degree focusing on marine particles collected in collaboration with folks at the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences (BIOS).

At BIOS, Fontánez got the chance to go on week-long research cruises, sampling ocean water and marine particles to study microbes that help sequester carbon from the atmosphere into the deep sea. While he loved the experience, Fontánez also shares how he couldn’t stop thinking about the dynamics of race and politics in science while there: “[BIOS] is mostly made up of people that are not from Bermuda –– they’re usually from Europe or the US and are there doing research. While they’re great people doing amazing research, it was disheartening to see that… I felt uncomfortable in the sense that [BIOS] felt like a bubble.”

Fontánez’s awareness of his own positionality coming from a colonized country grew as he started his PhD, which he is doing as part of the GEOPIG lab. For the PhD, he switched from studying marine microbes to microbes that survive in extreme environmental conditions: boiling hot hydrothermal systems like the hot springs in Yellowstone National Park.

While spending the summers in Yellowstone doing field work, he couldn’t help but feel like he was in an academic bubble once more. He started thinking more about the fact that Yellowstone was founded on land that was once home to Indigenous peoples like the Tukudika band of Shoshone, as well as people among the Crow, Blackfeet, and Nez Pierce nations.

“People were living here before this was a National Park, and they were displaced,” Fontánez remembers reflecting, “So then am I perpetuating this displacement because I’m doing this research here?”

None of the researchers around him were discussing such questions, pushing Fontánez to recognize how disconnected the field of geomicrobiology is from social justice issues. That’s motivated him to find ways of making his science applicable to real-world issues, in particular in Puerto Rico.

“My long term goal is to create a cooperative research institution in Puerto Rico that considers both natural and social components to take social action through science,” Fontánez shares, “Hopefully with the tools I gain in this PhD, I’ll be able to create a positive impact in Puerto Rico by understanding what Puerto Rican people want and need, and how we can work towards that.”

Since leaving Puerto Rico, Fontánez has spent years first developing his identity as a scientist, then realizing who he wants his science to be for. Now, he knows exactly who he is: “I am a proud, unabashedly Puerto Rican scientist,” he smiles.

Victoria Carvajal – Biology and Society: Ecology, Economics, and Ethics of the Environment track, MS

Like many of her peers and lab-mates, Victoria Carvajal, a master’s student in the Senko lab, fell in love with the ocean at a young age.

“Since I was about 15, I really loved the idea of biology. And eventually that morphed into the idea of marine biology, but I was always in denial about that because, you know, I was born and raised in Arizona. So, I was like “no, that’s overreaching.” But also, it was always in the back of my head.”

Though the origin of her interests is similar to many other young biologists’, Caravajal’s path has looked much different. When it came time to apply for colleges, Carvajal applied to some out-of-state marine biology programs as well as more standard biology programs, like ASU’s Conservation Biology and Ecology degree. Though she was given the opportunity to study marine biology out of state, life kept her from leaving.

“My freshman year of college was the COVID year, so I stayed local. I did everything with ASU online my first year,” she shares. “It also would have been impossible for me to go out of state, because I was full time taking care of my mom at the time.”

Carvajal’s mother was diagnosed with cancer when Carvajal was twelve years old. It felt like a miracle when the cancer seemed to subside throughout Carvajal’s teenage years.

But right as she was starting college again, the cancer relapsed. Her parents were divorced, and her mother’s family in Germany couldn’t travel to the US to help care for Carvajal’s mother because of COVID restrictions. That left Carvajal the job of both being a full-time student and a full-time caretaker for both her mother and her younger brother. Carvajal lost her mother at the end of that first year.

“My mother was such a light. The day I lost her, I inevitably lost a piece of myself. But the idea that she still lives on within me has kept my hope from slipping. It brings me happiness when I glance in the mirror and feel for a split second like I see her smiling back at me, wear a pair of her favorite earrings for a special day, or am told that I have the same laugh she did.”

Despite her grief, Carvajal continued with school. She had settled for the idea that she’d just be doing general conservation biology, nearly having given up her dream of doing marine science. But in 2021, she took a class on the Future of Oceans with Jesse Senko, a marine conservation scientist. After that class, Carvajal enrolled in a study abroad course Senko taught that brings undergraduate students to Baja California to learn about ecological and social aspects of sea turtle conservation.

“That study abroad trip brought me back to life. It was the first time I had been to the ocean after COVID, and the trip reignited a passion for sea life I thought I had lost,” Carvajal reflects, “After speaking one-on-one with a turtle poacher-turned-conservationist and witnessing artisanal fishing community dynamics firsthand, I knew marine conservation was what I wanted to do with the rest of my life.”[RS(1]

From that point on, Carvajal was hooked. She joined the Senko lab as undergraduate researcher with the plan of doing an accelerated master’s through the 4+1 program. Originally, she was going to join one of the lab’s projects in North Carolina studying whether attaching lights to fishing nets can ward off sea turtles, and reduce the amount of the creatures that are accidentally caught.

Since starting graduate school, though, Carvajal decided to stay longer, extending her time to two years so she can develop her own research idea. Now, Carvajal is doing a literature review on a different kind of technology meant to protect endangered species without negatively impacting the livelihoods of fishermen.

“There are these devices called turtle excluder devices (TEDs), which act like metal ramps inside this tunnel-shaped net that you drag along the sea floor to catch things like shrimp and flounder. So [turtles] won’t get caught in the net, and the device doesn’t damage the fragile shrimp that are the target catch. In addition to saving turtles, TEDs can save other animals too, but the ecological impacts are still not fully known.”

Carvajal is reviewing studies across the world that have observed that TEDs not only protect sea turtles, but other charismatic creatures as well. Though the future of academia and research is uncertain right now thanks to federal budget cuts and universities reducing the number of graduate students they’re admitting, Carvajal hopes to one day continue on to do her PhD with the Senko lab.

Though she’s had a hard road, Carvajal has found her way to doing the research she loves, research she was never she would get the chance to pursue.

“Though ASU wasn’t my first choice, I never looked back. I never regret it.”

And by doing what she loves, Carvajal is certain that she’s making her mother proud, too.